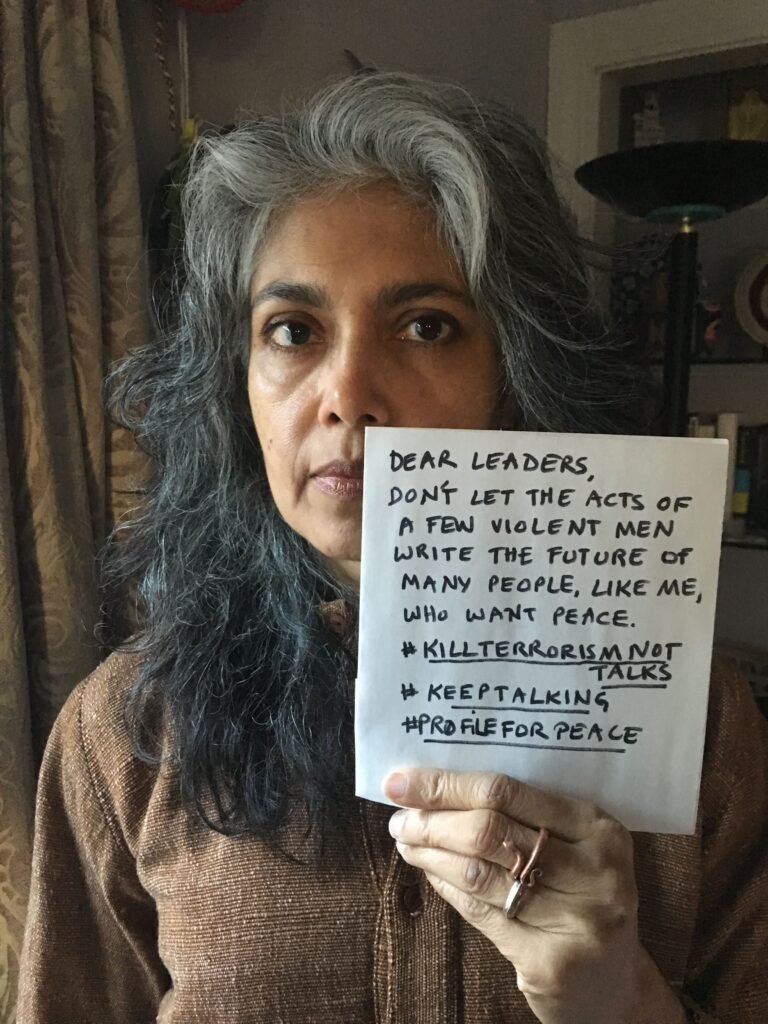

Dr. Shabana Parvez, MD, FACEP, US Bureau Chief of The Desi Buzz and founder of ArlingtonIntegrative.com, recently engaged in an enlightening conversation with Beena Sarwar—a journalist, artist, documentary filmmaker, and renowned human rights activist. Sarwar is the co-founder of the South Asia Peace Action Network and serves as editor for both the Sapan News Network and Aman Ki Asha (Hope for Peace). Her groundbreaking work has earned her several prestigious accolades, including the Media Transformation Challenge Fellowship in 2024 and the British Chevening Fellowship, highlighting her enduring commitment to promoting peace and social justice.

Dr Shabana Parvez: Welcome back to the Desi Talk Show. We have today a very special guest, Miss Beena Sarwar. She is a journalist, artist, documentary filmmaker, and a human rights activist. She is the co-founder of the South Asia Peace Action Network. Additionally, she serves as the editor of the Sapan News Network and also works as an editor for “Aman Ki Asha,” which stands for “Hope for Peace.” Miss Sarwar has received several prestigious fellowships, including the Media Transformation Challenge Fellowship this year and the British Chevening Fellowship in the UK, among others. As mentioned, she is also a documentary filmmaker, and we are thrilled to have her here today.

Let’s get started. Miss Beena, thank you so much for being here.

Beena Sarwar: Thank you for having me.

Dr Shabana Parvez: Thank you for taking the time. I am going to ask you a few questions about your career. You have a multi-faceted career as a journalist, artist, filmmaker, and teacher. How do you see these paths converging into your focus on peace?

Beena Sarwar: That is a really good question. I think what happens is when you are doing multiple things, but your underlying values are centered around human rights, social justice, human dignity, and peace, it all comes together.

You don’t have to beat someone over the head with it. It’s about treating everybody as equals and acknowledging their dignity as human beings. When you do that, everything else falls into place naturally.

Dr Shabana Parvez: That’s beautifully said. As the editor of “Aman Ki Asha,” what are some of the most powerful or impactful stories you have encountered that showcase the potential for peace between India and Pakistan?

Beena Sarwar: There is so much to talk about. “Aman Ki Asha,” was particularly impactful between 2010 and 2014, when it was at its peak. One of the most significant initiatives was the “Heart-to-Heart Campaign.” This campaign connected children in need of medical care with doctors who provided treatment, often free of cost.

It was a collaborative effort involving Rotary Clubs in India, Pakistan, and the United States. The process saved the lives of many children born with congenital heart defects. These children, often from rural families, received medical care and hospitality in India, which left a lasting impact on their families.

Dr Shabana Parvez: That’s truly inspiring. How do you envision the role of media in fostering dialogue and understanding between the communities in India and Pakistan?

Beena Sarwar: Media plays a critical role in shaping perceptions and fostering dialogue. Through initiatives like “Sapan News,” media groups helped move the peace narrative beyond intellectual discussions to involve real people and real stories.

Media initiatives like these allowed individuals to connect face-to-face, bridging gaps and creating lasting relationships. These connections often lead to a better understanding and shared humanity between communities.

But the connections are still strong, and people are still in touch. Social media enables people to stay connected. It’s not just about talking; it’s also about humanitarian efforts. For example, one of the big issues between India and Pakistan is the fishermen on both sides who get arrested and jailed. There are more Indians being jailed in Pakistan, not because Pakistan is crueler than India, but because more Indian fishermen cross the invisible maritime border. The security forces arrest them, and they’re calling for changes—like confiscating the catch and releasing the fishermen instead of imprisoning them.

Unfortunately, what happens is they get arrested and jailed, and their families have no idea whether they’re lost at sea, alive, or dead. They only find out when someone from the other side informs them. Sometimes, these fishermen spend years in jail without their families knowing.

Many of them are charged with illegal border crossing, and occasionally with espionage. Sometimes they die in custody on either side. These fishermen often don’t carry passports or visas because they’re out at sea to fish. After serving their sentences, there’s no simple way to release them. They need to be transported, given consular access, and verified by local authorities. This process, which could be digital and instantaneous, can take 2–3 months or more. Then, instead of being sent back home across the sea, they’re transported by bus or train a thousand miles to the Attari-Wagah border, where they cross into their home country. From there, they travel south to their villages.

If the crossing happens in winter, these fishermen—who’ve never experienced cold weather—are helped by local charities. In Pakistan, for instance, the Edhi Foundation provides blankets, sweaters, food, and sometimes money for expenses. This highlights the humanity of people on both sides.

Dr Shabana Parvez: You founded South Asia Peace Action Network to unite peace activists and address issues like these. What inspired you, and what are your goals for the network?

Beena Sarwar: I’m one of the co-founders of South Asia Peace Action Network. There were about 90 of us at the first meeting where we agreed to launch it. The group includes notable figures like Admiral Ramdas, former head of the Indian Navy, and Dr. Rubina Saigol, a sociologist from Pakistan, both of whom have since passed away. Others, like Kamla Bhasin, the legendary labor leader, have also inspired us.

Many young people were at that first meeting, and since then, more have joined. What gives me hope is that these young people often have no personal ties across the border—no ancestral homes, no family nostalgia—yet they want to work towards peace. They reject the divisive politics of today and believe in dialogue and mutual respect.

For example, if India and China or the US and China can trade and talk despite their political tensions, why can’t India and Pakistan? Unfortunately, every time progress is made, some incident derails it. It’s holding back the development of the entire region. Our neighbors—Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal—look at us and wonder why we can’t grow up and work together. It is a collaborative effort, and we do not just focus on peace. We address all issues, including hyper-nationalism and violence in the name of religion. We explore art and activism, music and mysticism, social movements across South Asia, sports, women’s challenges and victories, labor rights, the rights of the incarcerated, and education. It’s essentially about addressing all aspects of society.

Dr Shabana Parvez: That’s quite wide-ranging and amazing! It covers all sorts of issues across various walks of life and sectors. Essentially, it sounds like a humanitarian and socially conscious initiative.

Beena Sarwar: Yes, and we aim to cut across silos, whether in science, sports, or other areas. Sapan News, our media feature and syndicated service, grew out of this work. Initially, we issued press releases through South Asia Peace, but then I thought, why not formalize it as a feature service? Our slogan for Sapan News is: “It’s All Connected.”

Dr Shabana Parvez: That’s beautiful! What are some under-reported stories in legacy media that you wish to highlight?

Beena Sarwar: Sapan News isn’t a breaking news channel—we don’t have the capacity for that, and plenty of others are already doing it. Our initiative is volunteer-run under South Asia Peace and Sapan News. About 150 individual donors have contributed small amounts, and we’ve received support from organizations like the Institute for Nonprofit News and the Local Independent Online News initiative in America, where we’re registered.

This funding allows us to make some payments to part-time staff and contributors, but much of the work remains voluntary. We aim to cover and connect South Asia and its diaspora. Sapan News also explores the Indian Ocean and its diasporic communities. While we primarily focus on South Asia, we’re not restricted to it—we cover global issues and link them to the region and its diaspora.

Dr Shabana Parvez: That’s incredible. You also tell stories through film, as you are an artist and a filmmaker. How do you incorporate your creativity into advocacy, and what role do you think art plays in driving social change?

Beena Sarwar: Art and literature are essential. Without them, we risk becoming robots. Creativity is what differentiates us as humans—it helps us think outside the box, embrace nuance, and consider multiple perspectives.

In South Asia, there’s often a focus on siloing people into professions like engineering, medicine, or law. However, today, many young people are breaking out of these molds. They want to pursue acting, filmmaking, and other creative outlets. Creativity captures imaginations and drives society forward.

Dr Shabana Parvez: It’s not just black and white—it’s about holding space for different perspectives.

Beena Sarwar: Exactly. A lack of nuance leads to cancel culture and outrage culture. People are quick to react without understanding the context. For example, no religion justifies violence, yet we see violence committed in the name of nearly every religion.

After 9/11, I wrote an essay for a book titled Dispatches from a Wounded World, discussing how religion in Pakistan was hijacked. Religion, in its essence, does not condone violence. To understand this, we must look at the context and use our reasoning. Violence isn’t justified by any religion when viewed in its entirety. And the people who are engaging in these actions are often convinced of their righteousness because they believe they are right and everyone else is wrong. I think it is essential for human evolution to recognize the shades of gray. Not everything is black and white. It’s about pausing, reflecting, and considering different perspectives. It’s also about highlighting the compassionate and merciful aspects of humanity—the Rahman and Rahim principles.

Dr Shabana Parvez: Exactly. If we continue to respond to violence with more violence, this cycle will perpetuate itself. Instead, we need to address the root causes of the violence. Why did it happen? Why did someone become an abuser? It’s about treating from a place of love and seeking inclusive, non-violent solutions that create win-win outcomes for everyone.

Beena Sarwar: Yes, absolutely—compassion is key. And empowering children is crucial. Often, child abusers are people known to the family or the children themselves. These individuals exploit the trust and power they have over the child. We must teach children that it’s okay to speak up, that they will be believed, and that they are not to blame. We need to avoid shaming them by saying things like, “How could your uncle, grandfather, cousin, or father have done this?”

Dr Shabana Parvez: That’s a significant issue in many cultures. Discussions about abuse are often taboo, which only makes addressing the problem harder.

Beena Sarwar: Yes, exactly.

Dr Shabana Parvez: Beena, could you tell us about your documentary, Milne Do – Let Kashmiris Meet? It seems to encapsulate your mission for peace.

Beena Sarwar: Yes, Milne Do does reflect that mission. It’s a slogan we adopted at Aman Ki Asha as well. The documentary is very short—only seven minutes long—and was made with minimal resources.

Dr Shabana Parvez: What are your aspirations for the future? How do you plan to continue promoting peace initiatives through your work?

Beena Sarwar: One of my most recent films was about Sri Lanka. People often find it unusual for a Pakistani to make a film about Sri Lanka unless it’s for tourism purposes. This film, however, was made in collaboration with local researchers and consultants. That collaborative approach—working from the ground up and entering these spaces without a set agenda—is something I want to continue doing. It’s about giving people a platform to share their stories in a universal way.

I also teach global journalism at Emerson College. For me, global journalism is about connecting the dots—going beyond just reporting events to uncover the underlying stories and voices.

Dr Shabana Parvez: That’s incredible. As a physician, I’m curious—how do you maintain your physical, mental, and spiritual health while doing such impactful work? And what is your secret to success?

Beena Sarwar: I don’t know about success—it means different things to different people. My father, who was a physician, led Pakistan’s first student movement while in medical school. That activism is in my genes. My mother, a pioneering teacher trainer, founded Pakistan’s first teacher training institution, the Society of Pakistan English Language Teachers, which celebrates 40 years this November.

As for health, I’ve been recovering from a cold that’s lingered for two weeks! But over the years, I’ve learned to focus on being grounded and strong at my core while staying flexible. It’s about adapting to challenges, not reacting impulsively. For instance, at Aman Ki Asha, instead of reacting to negative events, we try to create our own positive narrative.

To me, it’s all about being proactive, keeping doors to dialogue open, and maintaining a spirit of collaboration. That’s what keeps me going.

Dr Shabana Parvez: On a daily basis, as you mentioned, how can the average person contribute to fostering peace, especially between India and Pakistan? Our audience is largely South Asian, so what can they do in their daily lives?

Beena Sarwar: I think people can just do what they can—help where they can, support others, and use their voices responsibly. I’m not saying we are the only solution. For example, our initiative Sapan News is a feature-syndicated service. We send our features to various editors, bloggers, and other platforms, allowing them to use it for free. Ideally, we’d love for people to contribute financially to our work, but we understand the constraints in South Asia, where even journalists often go unpaid for exclusive content, let alone syndicated features.

The point is to get the narrative out there. If someone has an article idea or a video they want to create, they can pitch it to us. We work with contributors to amplify their voices. It’s about uplifting one another. For instance, the South Asia Peace Action Network has nearly 100 organizations endorsing its founding charter, which emphasizes people-to-people connections, economic cooperation, human rights, and dignity. All of this has grown organically through volunteer efforts and word-of-mouth without marketing campaigns.

Dr Shabana Parvez: That’s amazing. It sounds like you’re just getting started, and there’s so much potential for growth.

Beena Sarwar: Exactly. If this resonates with anyone, they’re welcome to join us. The Sapan charter is available in multiple languages—Bangla, Sinhala, Punjabi, and others. We encourage people to participate in our discussions, even if they don’t speak English. We can arrange for translations. We host public discussions on the last Sunday of every month, and anyone can subscribe to our newsletter or suggest improvements.

For instance, if you know someone who can help families facing visa issues, they can make a huge difference. I know of a family where the husband is in India while the wife and daughters are in Pakistan. They’ve been separated for years because of visa restrictions. There are countless such stories, and a small act of kindness could reunite families.

Dr Shabana Parvez: That’s heartbreaking—just one of many stories like that.

Beena Sarwar: Absolutely. And addressing another issue—social media. Over the past 10–15 years, we’ve gained a lot through connections, but we’ve also lost a lot. Social media often triggers fear, outrage, and anxiety, privileging the reactive “reptilian” part of our brain. People share, react, and amplify negativity, and this has taken us backward in some ways.

To counter this, we developed a Social Media Code of Ethics. It’s a simple checklist that helps users—whether journalists or regular social media users—approach online interactions responsibly. Many senior editors have found it useful, saying it helps them remain mindful even in heated online discussions.

Dr Shabana Parvez: That sounds brilliant. Humanity and decency have often taken a backseat in the online world.

Beena Sarwar: Exactly. Our hope is that by signing onto this code of ethics, users can display a widget on their profiles that says, “I abide by the Social Media Code of Ethics.” It’s currently a Google Doc that we’re working to make public. It’s still a work in progress, but the idea is to create a community of users who pledge to foster a healthier online environment.

Dr Shabana Parvez: It’s a much-needed initiative.

Beena Sarwar: As for advice, it’s not just the younger generation—it’s also older generations who need to reflect on their actions. Platforms like Facebook and WhatsApp are rife with forwarded messages spreading outrage. Interestingly, younger people are showing us how to behave by moving away from such platforms.

To aspiring journalists and activists, my advice is simple: never assume you know everything. Keep learning. The Social Media Code of Ethics, for instance, has benefitted from input from both young and senior contributors.

I also tell my journalism students to focus on the process behind events, understand the context, and take the long view. That’s how we can create meaningful, lasting change.

Dr Shabana Parvez: That’s excellent advice—always learning and striving for better.

Beena Sarwar: Thank you. We’ll share links to these initiatives so your viewers can join or support them. It’s all about building a compassionate, responsible community.

Dr Shabana Parvez: Absolutely. Thank you so much for sharing your insights.